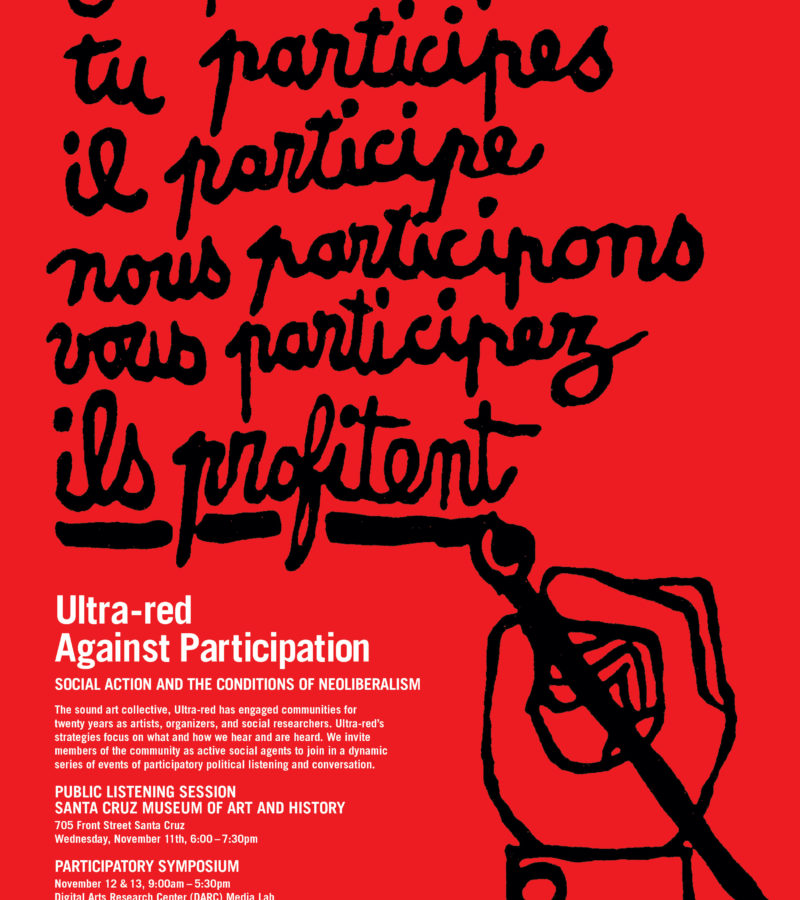

Hannah Arendt, in her analysis of the human condition, wrote that to live a life that is entirely private, or invisible to others is: ‘to be deprived of the reality that comes from being seen and heard by others…to be deprived of the possibility of achieving something more permanent than life itself’.

It is hardly news to say that, globally, public spaces prioritise the voices and lives of certain communities over others, making both the achievements and pain of the disenfranchised harder to see or hear. Even attentive reading of the recent headlines covering the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis at the hands of the police, or the disproportionate number of deaths from COVID-19 among BAME communities, can make one aware of the extent of the consequences of inequality due to systemic invisibility.

Universities, can use their relative autonomy to create a disruption within existing systems. Universities can provide a platform for the seemingly invisible, allowing them not only to voice their rights but also to build a legacy that will continue beyond individual lives. This essay focuses on a case that illustrates just that. It studies a university commission, a bronze, outdoor sculpture — Students Aspire, 1978 by Elizabeth Catlett — as an example of positive reinforcement of equality. Besides reflecting on the role that the work played in the physical space of the Howard University campus, this essay considers what impact Students Aspire can have as a digital being, present in an online teaching environment.

Catlett spoke in 2010 on the subject of invisibility in the context of her portraiture of Black women. Her early series of linoleum cuts, titled, The Black Woman (1946–47) remains among her most celebrated works. Catlett reflected: ‘When I decided that I am going to work with the problems of Black women, I was going to try to make people see them as beautiful, dignified, strong people instead of, as Ralph Elisson says, invisible’.

From the early stages of her career, positive representation of her own community, its labour and rights was central to Catlett’s work; however, it was not always easy for her to find a supportive outlet to promote her vision. One of the most encouraging environments that she recalled was the Howard University School of Engineering, which commissioned and erected Students Aspire.

Howard was the first American university to offer an engineering degree to Black Americans. It was founded in 1867 by a controversial Civil War general Oliver O’Howard, an abolitionist who famously wrote in a letter to the New York Times in 1863, ‘We must destroy Slavery root and branch…..This is a hard duty — a terrible, solemn duty; but it is a duty’.

Catlett was one of the students whose life was positively changed by university and its mission to champion human rights. The university secured a place for her when she had not been allowed to enrol — despite winning a scholarship — at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh, because of the colour of her skin. Almost thirty years after her graduation from Howard, Catlett was selected, by a ‘vote of the faculty, students and staff’, from a group of twenty artists whom Howard approached in 1974 to commission a piece for the university’s newly built Chemical Engineering wing.

The university had decided to solidify its core values in the material form of a public commission. As explained by Dr James E. Cheek, President of the University:

The artists who were invited to participate in the competition were charged with creating a sculpture which would be symbolic and expressive of the purposes of the School of Engineering of Howard University and which would reflect and be emotive of the struggle of Black Americans, and the sacrifices which they have made to give expression to their inventive and scientific gifts.

In response to the call, Catlett depicted two students, a woman and a man, embracing each other and lifting their hands to support a symbol of equality. We can see them flanked by the emblems of mechanical, civil, chemical and electrical engineering. The emblems form a triangle and, following Catlett’s own interpretation, are meant to represent the upper branches of a tree. The bodies of the students form the trunk and stand on a foundation representing the roots. The roots are sprouting from twelve masks, each representing one Black scientist. It is a testimony of the sometimes inhumane effort, brilliance, work and persistence, the legacy of which was to allow the next generations to get closer to the goal of attaining equal rights.

The press release for the show quotes Catlett herself describing the objective of this work:

The two students are holding each other up to express unity rather than the competition that exists in education. The equal sign signifies scientific as well as social equality — that everybody should be equal; men to women, students to faculty, blacks to everyone else.

Through her commission, Catlett presents the excellence and right to equality of Black students as a status quo governing the university. The level of the institutional commitment is reflected here in the material — bronze — which allowed the sculpture to persist for over forty years. Significantly, Catlett’s protagonists are the students themselves, who can see themselves reflected in the work, as the artist intended. They are the everyday heroes who upon graduation from the university will do their best to pursue their dream careers. The title expresses their longing for a future, in which equality might become a reality.

Catlett believed that her role as an artist was to support people’s emancipation and that visualising struggle in the public eye was one way to achieve that. As she wrote in her article, The Role of The Black Artist, 1975:

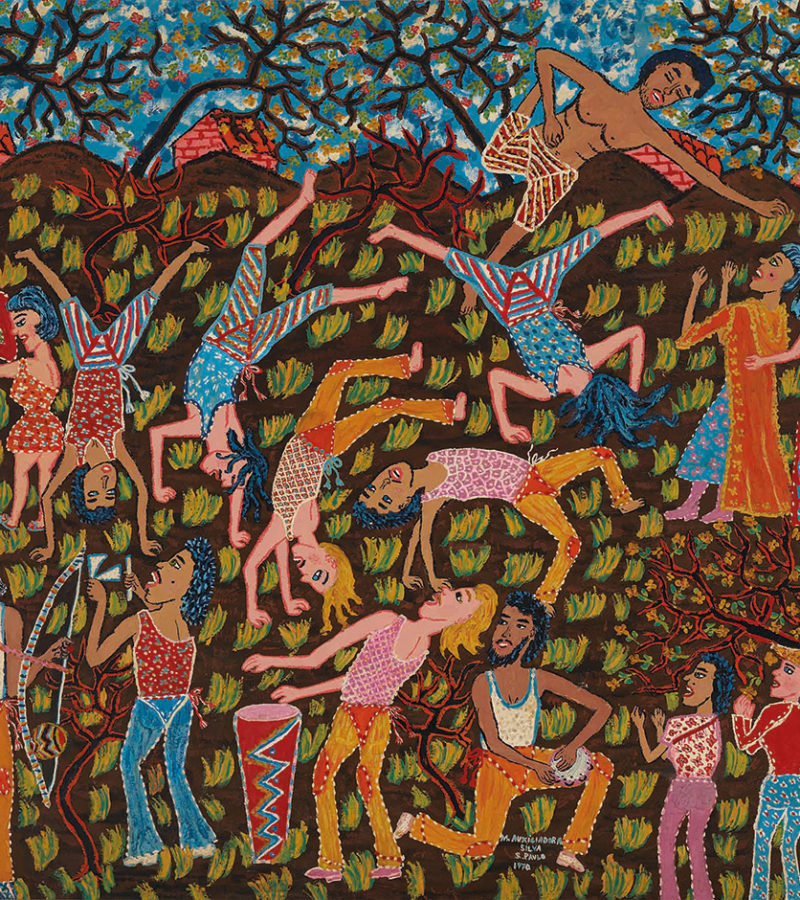

We must learn from inside the struggle because of its changes as the people change. Only as a part of the mass can we recognize its needs as to our artistic contribution. Because art needs to be public to reach the majority of blacks, regardless of class, the artists are taking art to the streets in mural painting, to the churches and other meeting places. They are working in cultural centers with both children and adults; some are bringing a chance for artistic expression into the prisons. We must go where black people are. Our struggle is not for black culture but for black liberation.

During the Civil Rights Movement and beyond, interventions in the public sphere such as sculptures and murals played an unprecedented role in disseminating alternative imagery of Black Americans to that promoted by the mainstream media. Artists took up the goal of changing the immediate environment of the people. One of the earliest inspirations pointing Catlett in the direction of public commissions were the Mexican mural paintings she discovered as a student at the Library of Congress in Washington. In Students Aspire, however, Catlett seems also to be referring to an iconic work of socialist realism, Vera Mukhina’s Worker and Kolkhoz Woman, created for the 1937 World’s Fair in Paris. The sculpture, made of stainless steel and measuring 24.5 metres high, shows a man and a woman raising their hands in just the manner of Catlett’s students; a woman is holding a sickle, and the man a hammer — gestures symbolising their equal contribution to the revolution. Mukhina’s public commission, made with a view to exporting Soviet principles abroad, offers a glimpse of a very different perspective on women’s role in society. It is often forgotten that, as Leon Trotsky reported across The History of The Russian Revolution, 1930, that the October Revolution of 1917 was led and sustained by brave women workers and that the movement itself started on International Women’s Day.

The visual language of Students Aspire nods to a revolution that was designed to stir a global fight for an equal world. This stylistic and ideological decision of Catlett’s showed the fight for the visibility and equality of Black American citizens as an important part of a worldwide solidarity movement and allowed Catlett to communicate to global audiences a struggle known to her first-hand. In the previously quoted The Role of The Black Artist, Catlett expressed an intention to reach beyond her immediate audience, arguing that ‘Culture can be a beginning for our involvement with other peoples who share with us racial or national discrimination’.

The global reach of Catlett’s voice and her advocacy, having started from the modest site of a single university, takes a new turn in the context of a digitalised world, and its teaching environment. As much as we would like to believe that the internet, as a technology, is free from the prejudice that corrodes the fabric of our physical world, there is much evidence to prove the opposite. Consequently, just as in the real world, the autonomy of universities to act as virtual enclaves of equality needs to be defended.

Digitalisation has increased the reach of Catlett’s work beyond the campus and beyond Washington. If integrated into the school curriculum, the work might function in similar ways to the physical sculpture seen by students on their way to class. It maintains the potential to encourage and engender pride. It can also continue to inspire global conversations. André Brock Jr. argues that ‘Black online culture and sociality are more easily visualized today thanks not only to the hashtag and other algorithmic means but also to the near infrastructural use of social networking services’. Despite the truth of this statement, I am finishing this essay on a day when the use of hashtag #BlackLivesMatter was suddenly interrupted on the popular platform TikTok by what was described as a ‘technological glitch’; a day when citizens of 25 cities across the United States took to the streets to fight for their rights, in light of the recent killing of George Floyd.

Although the video that made visible the perpetrators of this killing played an instrumental role in their arrests, it did not stop the police from inflicting more violence in the days that have followed. Catlett dedicated her life to championing change, and although students still need to aspire, rather than having already gained the equality and visibility they deserve, her cause is not lost. Her commission and her own experience at Howard remain examples of the positive and powerful impact universities can have on individual lives. Catlett left her oeuvre, as an artist, a teacher, and an activist, for the current generation to build upon, to open up more spaces, claim them, be visible and proud; to populate the public and digital sphere with imagery of their choice.

- 1. Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition, University of Chicago Press, 1998, p.58.

- 2. See Hannah Devlin, 'Why are people from BAME groups dying disproportionately of Covid-19? The Guardian, 22 April 2020, available at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/22/why-are-people-from-bame-groups-dying-disproportionately-of-covid-19 (last accessed on 3 June 2020).

- 3. Catlett refers to Ralph Ellison’s book Invisible Man, 1952. See 'Elizabeth Catlett: My Advice to Young African Americans’ [online video] available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EAl9xr5dbx8 (last accessed on 3 June 2020).

- 4. See Daniel Sharfstein, ;The Namesake of Howard University Spent Years Kicking Native Americans Off of Their Land’, Smithsonian Magazine, 23 May 2017, available at https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/namesake-howard-university-spent-years-kicking-native-americans-out-180963409/ (last accessed on 3 June 2020).

- 5. See Karen Rosenberg, ‘Elizabeth Catlett, Sculptor with Eye on Social Issues, is Dead at 96’, New York Times, 3 April 2012, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/04/arts/design/elizabeth-catlett-sculptor-with-eye-on-social-issues-dies-at-96.html (last accessed on 3 June 2020).

- 6. Program for the unveiling of Elizabeth Catlett’s sculpture Students Aspire, Howard University School of Engineering, 1978.

- 7. Ibid.

- 8. See Jordan McDonald, ‘Elizabeth Catlett’s Students Aspire and the (Black) Artist as Engineer’, Archives of American Art website, available at https://www.aaa.si.edu/blog/2019/02/elizabeth-catletts-students-aspire-and-the-black-artist-engineer (last accessed on 3 June 2020).

- 9. Elizabeth Catlett, ‘The Role of The Black Artist’ in The Black Scholar, vol.6, no.9, June 1975, p.12.

- 10. Catlett in the quote above seems to be referring specifically to Faith Ringold’s For the Women’s House, painted in 1971, depicting women occupying a variety of professions. The painting was executed in response to the wishes of inmates of Correctional Institution for Women on Rikers, who wanted to see a hopeful image, ‘a long road leading out of here’. See https://hyperallergic.com/399211/keeping-faith-with-ringgold/ (last accessed on 3 June 2020).

- 11. See ‘Elizabeth Catlett: Legends at Howard University’ [online video], available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_ew5QmH184o&t=1s (last accessed on 3 June 2020)

- 12. See Sylwia Serafinowicz, ‘The Socialist Woman and the longest caress in the history of French cinema’, in Not.Fot. vol.7.

- 13. Leon Trotsky criticised abuse of Black Americans on many occasions, including A Letter to the American Trotskyists, 1929 and Manifesto of the Fourth International, 1940.

- 14. E. Catlett, ‘The Role of The Black Artist’, op. cit. p.14.

- 15. André Brock Jr., Distributed Blackness: African American Cybercultures, New York: NYU Press, 2020, p.2.

- 16. See 'Fact check: The #blacklivesmatter hashtag is not banned on TikTok’, Reuters Fact Check, available at https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-factcheck-tiktok/fact-check-the-blacklivesmatter-hashtag-is-not-banned-on-tiktok-idUSKBN2360OT (last accessed on 3 June 2020).