The year 2020 sent waves of vibrations reverberating through the world. Following the death of George Floyd at the hands of the police and the subsequent protests initially led by the Black Lives Matter movement in the US but widely spreading at an unprecedented speed across the globe, enterprises, institutions and organisations in the Global North have frantically clung to promises of ‘inclusiveness’ and ‘diversification’ in a bid to remain relevant in a time of seismic political, social and cultural upheaval. In the last year we have been witnessing numerous performative attempts on the part of institutions, all swallowed up by half-hearted attempts to confront their own imperialist and/or capitalist structures, to align with new discourses and terms of discussion. Such institutions, however, have shown little ambition to challenge the long-standing histories that allowed them to form in the first place – situations where Black and brown bodies continue to be subjected to various forms of violence. The publishing industry is no exception.

A Contested Terrain

Publishing is inherently political; an instrument of power. It is a contested terrain in which power is continuously negotiated, where ideas of ‘collective’ memorialisation are nurtured, and where most of the global population continues to be silenced. In some ways, publishing remains a site in which history travels through time in a circular trajectory, continually returning to its epicentre: to the terms of its foundation. Through acts of publishing, the legacies of imperialism and colonialism are reproduced in new forms in contemporary political and cultural languages. This particularly takes place in societies where the too familiar North-South discrepancy continues to spiral, where shifts in predominant narratives in the mainstream media landscape rarely occur, not allowing for crucial stories of liberation, decoloniality and insurrections to unfold. From such a perspective, I’d like to offer some reflections that critically interrogate not only who dictates which stories are deemed relevant in the twenty-first century, but in addition, why? From which position do they speak, and what are the consequences of such positional bias? Conversely, whose voices are being heard, and how are the voices that do emerge given greater or lesser legitimacy, or even rendered invisible in the construction of global narratives?

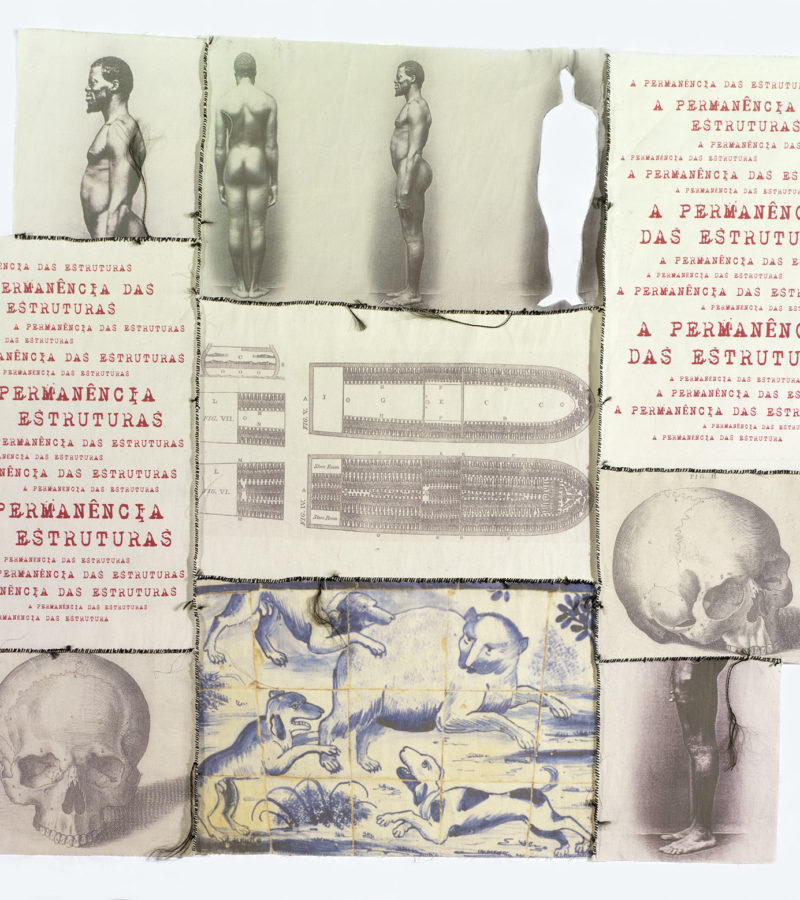

Rewinding through history, the act of publishing and related forms of knowledge formation have historically been at the centre of the colonial project. Strongly tied to colonial impulses, publishing has been inextricably linked to various forms of violence enacted on racialised bodies. Tracing back these legacies, colonial powers have dictated literary production, systematically applying censorships and monopolistic grips on critical discourses and other forms of knowledge production. To this end, the act of publishing has thus taken shape as a territory of domination advancing Western ideals that silence millions of voices deemed subordinate. Yet today, we are still confronted with ignorance as to how to respond to paradigms of structural injustice and dismantle systems of racism which are profoundly upheld by cowardly tendencies to remain neutral or the unwillingness to proclaim solidarity across strata – from private enterprises, to civic institutions, including universities and museums, as well as in spheres, such as the culture industry, that straddle both sectors.

Yet, much can be learned from the histories that precede our time. The Pan-African project, for instance, is one of many examples of a form of planetary imagination from which we can still learn. From within this framework, the literary outputs of Frantz Fanon, Aimé Cesare, Amilcar Cabral, Léopold Sédar Senghor, among others, informed progressive publishing in such a way as to serve as crucial tools for resistance against colonial domination. From such a perspective, publishing became a site of potential progression in liberation struggles. It not only allowed colonised bodies to understand their own political realities, but moreover enabled them to organise and ultimately to struggle against those realities. In this sense, publishing became a weapon for liberation. In my view, a noble and critical task in challenging existing knowledge paradigms might be to stand on the shoulders of these historical figures and their legacies to revisit the transformative potentials inherent in the act of publishing. It is essential to nurture alternative forms of narrative relevant for the times in which we find ourselves; narratives that aspire to be useful and foster internationalist solidarity.

Revisiting the Politics of Content and Form of the Publication

Publications are here to relay, produce and curate knowledge. However, in focusing exclusively on the ‘optics’ of who is involved in this process – on representation and ‘diversification’ – the publishing industry tends to neglect the material operations fundamental to the industry, the question of how knowledge is produced and disseminated and the implications of these processes in foundational structures of violence.

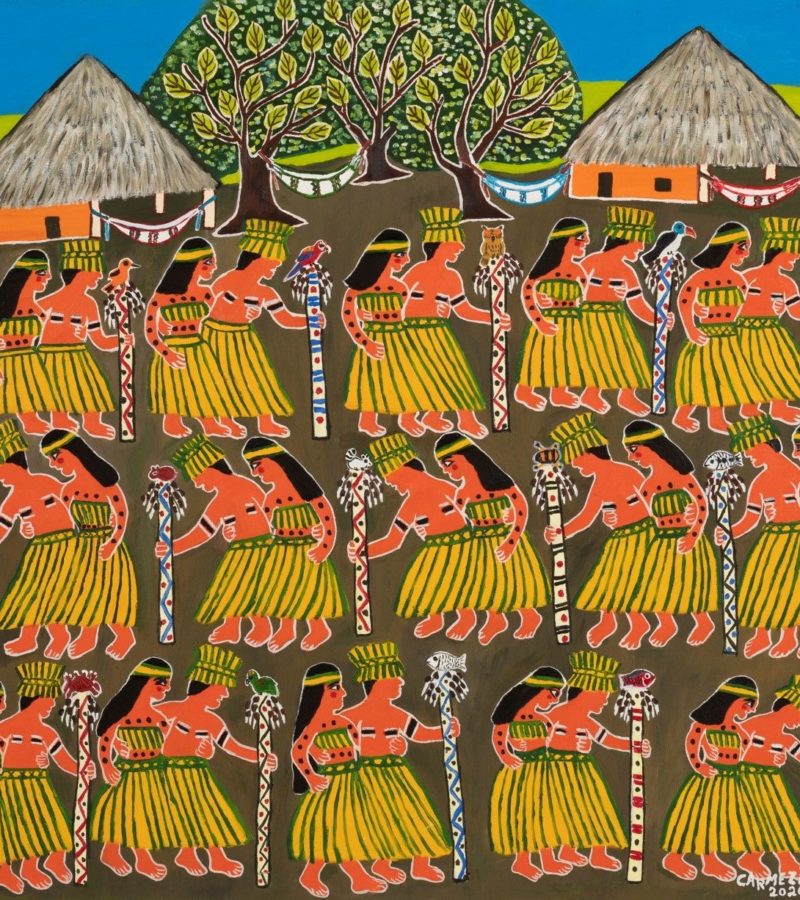

Yet at this particular moment of performative ‘reform’, such a tendency might be punctuated with inflections – moments of suspense and possibility for crucial turns. It seems timely to think about the agency of the publication in the 2020s, along with the question of its relevance in societies where racialised subjects continue to be targets of various forms of state and normative violence. How do we strive to curate alternative stories that extend the agency of publication to the marginalised subject? How do we lend this power to stories that allow us to understand the world through multiple voices, angles and perspectives when curatorial practices at their core are bound to an epistemological foundation, a knowledge base, defined by a Western gaze?

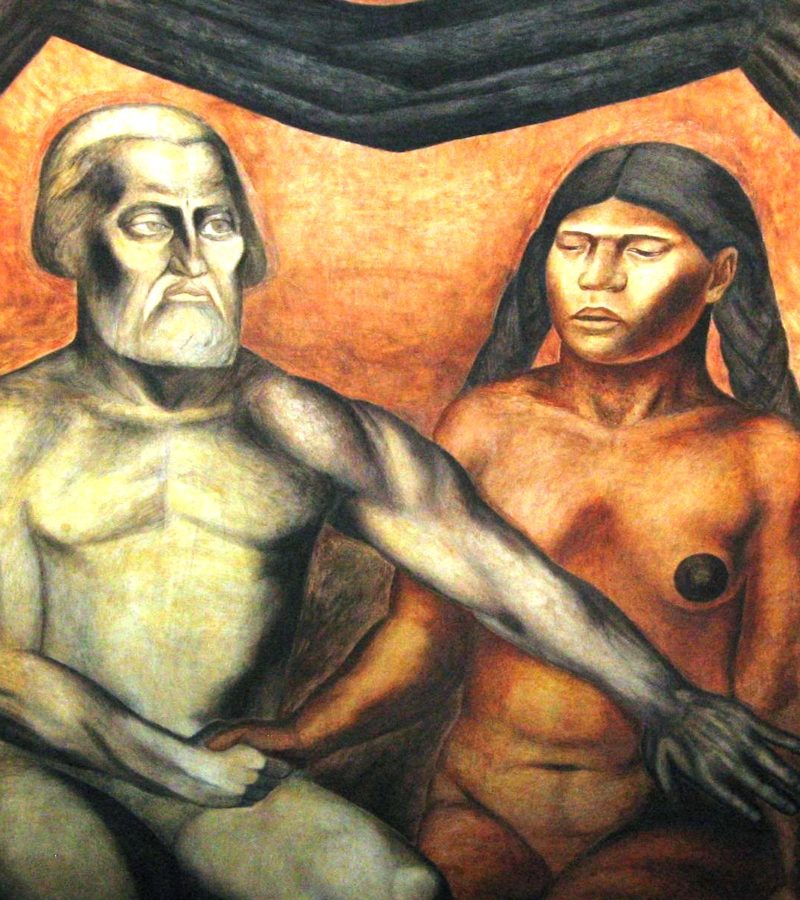

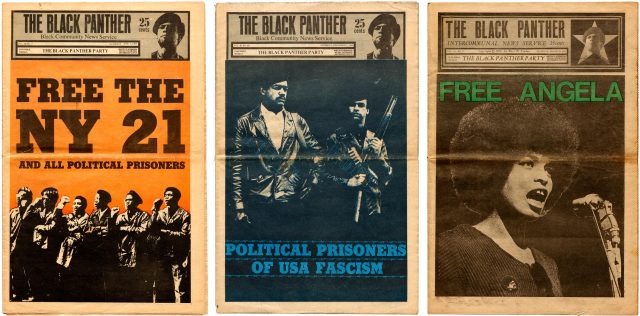

There are moments of potential for the narrative to change. Crucial to the transferability of historical lessons – their transformative, even revolutionary potential in the present – are the infrastructures of global circulation of ideas nurtured through the act of publishing. Looking back at some influential publications that explicitly attempted to serve a given political struggle, from The Black Panther newspaper, to the Pacific Indigenous Periodicals and Présence Africain, to name a few, it seems that all these models for decentring existing modes of knowledge formation were able to move beyond a particular geography. While taking shape primarily as socio-political interventions, these showed a crucial ability to move beyond the idea of the nation-state so as to build networks of transnational solidarity among bodies at the forefront of political struggles. Hence, what proved to have been vital for many of these publications were logistical infrastructures that advanced the dissemination of progressive thought. That is, equally important to the contents of a publication are the politics of form and distribution.

While acknowledging their limitations, we ought to pay deliberate attention to the logistical chains and operational processes driving the publishing industry. Which ethical considerations should be taken into account in processes of commissioning, editing and producing? What choices are being made to generate revenue; who is part of the decision-making processes and why? In answering these questions we must confront the capitalist structures that order logistical chains – not only the reimbursement of contributors, salaries paid to the members forming editorial teams, but in addition, the working conditions of those external but indispensable to the industry itself, from the labouring bodies involved in printing operations to those involved in distribution. Within this confrontation, and thinking through the chains of labour that constitute the industry, ethical considerations must remain at the centre. Publications entangle a vast range of political, ethical and social formations of production.

In conclusion, decoloniality is a process. It is a notion that asks us to recalibrate at many different levels. It is a multifaceted process forcing us to move beyond hollow promises of inclusion to ultimately rethink the way we tell stories. It is a process with a view to dismantling existing hierarchies and regimes of power, never compromising in this effort, or succumbing to a Western gaze and its inherently violent impulses.

![[Description: Black and white photograph of people looking out of a window]](https://www.afterallartschool.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Thomaz-Farkas_Rahul-Rao-800x900.jpg)

![[Description: Valeska Soares, Duplaface (Branco de titânio), 2017. Oil and cutout on existing oil portrait, 71 x 56cm. Courtesy MASP]](https://www.afterallartschool.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Osmundo_Valeska-Soares-800x900.jpg)